Box Canyon Creek (into the Chetco). High water, ropes and helicopters, oh my!

The Kalmiopsis Wilderness is vast, rugged and steep. I am always grateful to get a chance to visit her again. I had been wanting to do the Chetco, and heard of an alternative. This spring, a group did a tributary to the Chetco called Box Canyon Creek. After reading the article and seeing their photos, I was intrigued to see a different section of the wilderness.

Box Canyon Creek basically parrallels the Chetco River. It is about 7 miles long and the beta we had mentioned class IV/IV+ rapids without much discussion of wood. They recommended higher flows (possible as high as 10k). I thought the same after looking at the photos. The other bonus was only a 4 mile hike versus a 9 mile hike to the Chetco headwaters.

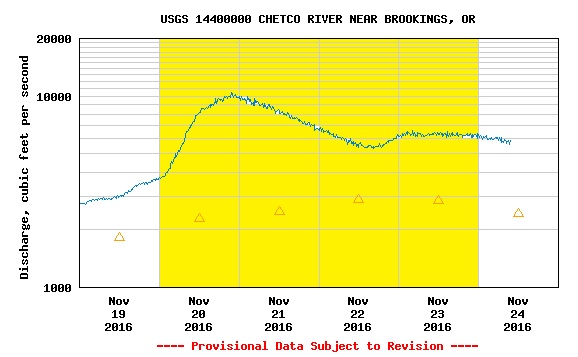

They had 2500 – 5000 cfs on the Chetco gage for the Box. Keep in mind that the Chetco gage is way down stream, and not a reliable source of information. It serves as only an indicator. With flows “predicted” to peak at 6000 cfs I thought we were set up for a great level. With more flow and their beta—David and I thought we could knock it out quicker than they did. We were planning on only one night.

I picked up David Fomolo at 5am. He worked passed midnight the night before and was running on only a few hours of sleep.

We dropped a car at the South Fork Chetco and the Chetco confluence before driving up toward Vulcan Lake. The road we drove was rough, narrow, and no shorter than 15 miles. With the time of year being late November, we were surprised to come up behind a Dodge truck a few miles before the road dead-ends.

When the road ended, I hopped out of David’s truck to talk to the guys. They were rough looking characters. However, coming from West Virginia, I learned to never judge a book by its cover. The guy in the passenger seat was older with what looked to be a burned right eye. He had a rifle in his lap and a pistol on the dash. The gentleman driving was younger. The older gentleman asked where we were going. I explained, and then asked what they were up to. He said, they were hunting and that his family use to own the Gardner Mine up by Vulcan Lake. He was happy to relay some of his family history on the area before the wilderness designation–and I was happy to get the history lesson.

He said that he wouldn’t go in there this late in the year—despite what the weather was doing (It was down-pouring). I mulled over his warning.

David has a two-seater truck and it was dumping buckets. Lucky for us, there was a dilapidated shitter at the trailhead. Dave and I were both able to fit in it to get situated and changed for the mission. We finally attached backpacks to our boats and headed out.

The hiking trail (~2 miles) was pleasant. I’m sure the scenery would have been grand had it not been socked in with clouds. Visibility was extremely low. We got slightly off trail. We took a wrong fork and lost the trail due to the scene of the Biscuit Fire. After a little bush whacking, we were able to meet back up with it again. We eventually made it to the point to start the cross-country hike (~1 mile). We knew we wanted to hike down a ridge line—but due to poor visibility, we couldn’t tell which ridge line to descend. We missed slightly and ended up in an inconvenient ravine. Traversing it was difficult but we eventually made it to Box Canyon Creek.

At the put-in, we could see that the water level was high. We scouted the first section as far as we could see. We had to run the first 3-4 drops all at once to get to the first eddy. I went first and caught the eddy, David came next and said he flipped and had to roll. I ran the next manky drop and eddied out. In front of me were two drops that lead into a river wide log. David came down the shore to scout and check on me. I showed him the log and we discussed our options. The only way to pass it would be to flip when you got to the log and then roll up after it. It was questionable whether there was enough clearance to even pull that maneuver off. Portaging was questionable because the walls were straight up.

We both agreed that the water was too high and it would be best to camp and let it drop. We decided to set camp and reevaluate in the morning. Having only traveled about a half mile—it wouldn’t have been too bad to hike out if things did not improve the next morning. It pitter-pattered rain all night. In the morning I was skeptical that the water would drop enough. We were still trying to decide whether packing boats and gear out would be better than leaving boats and coming back for them in the spring.

In the morning, when we reevaluated the rapid—it looked much more manageable and you could now barely duck under the log. The green light was back on. David carried the manky drop and we ran the rapid and ducked the log without incident.

We got into a rhythm. The water level was still high, but doable. We made it to a really steep, long section. The upper part was a mandatory easy portage river right. We then had to start from river right ferry across some fast current and then drop over a few drops, just flying along. It was our first great rapid and brought smiles all around. I caught an eddy to set safety for David. He opted to carry past me. We encountered a few logjams here and there, particularly where there were islands (I think there were 3?).

There was one newly formed rapid where a landslide had formed and pushed the river bed over to a new channel. The water was fighting to clear a new path between the trees and boulders. This was the easiest portage on the run.

We then got down to a narrow squeeze that had a severe undercut on the right. It was also a mandatory easy portage river right with a seal launch after.

Shortly after this, things started to gorge up. We then arrived at a pinch that fed directly into a wall. The water was violently ricocheting off the wall. You had to enter the pinch and get your nose left to brace/ride it out. The violent surge of water would have made it difficult to stay upright. The difficulty was a deflector rock in the approach that wanted to send you right. If you got caught in the right swirl it looked, bad—real bad. There was eddy service before this rapid—both on the right and left side of the river.

We were able to get above the canyon on river left—out far enough to look down the canyon. It was difficult to see down the canyon here because it “S” turns back and forth. The next rapid after the pinch was straightforward. There was another rapid with a log you could duck—and around the corner you could see a ledge drop with exploding water below it’s horizon line. It was hard to see it from the top of the canyon. It looked big, but straight forward.

There was a spot for us to drop kayaks down on river left after the pinch. If we did that, we would have to commit to running the ledge drop. It looked like there was no getting out before the ledge drop once you were at water level again.

We once again discussed our options. We both thought we had to carry the pinch. If this was the start of the main gorge, we felt there was still too much water. We felt we needed to camp again and hope for the water to drop again.

We debated between carrying our gear and boats around the portage that night, or waiting until morning after the water had dropped. We could not tell from above if there were any good sleeping spots down below on the launch rock. We opted to sleep above, and determine further in the morning.

We had to scrounge around that night for a spot to sleep two bodies. We found one up river. There was not a spot big enough for the both of us to sleep side by side. We were hoping to share our one rain tarp. David had a bivy and I opted to chance it—sleeping out in the open with the tarp beside me in case it rained. We were very thankful that night. It was the only time in our whole trip that it was not raining.

In the morning, we noticed that the water level had dropped again. After scouting the pinch drop in the morning, we decided it looked difficult—but more manageable. It is definitely runnable. Because the water level dropped, I discussed a new option with David. The plan was to drive my boat center and dry out on the rocks above the pinch drop. From there, I wanted to scout the right side and then eventually help David make the same move by grabbing the bow of his boat once he hit the rocks. From there, we would have to go up a little ways and drop back down to a seal launch about 10 feet above water level. Though more dangerous, it would make the portage much easier.

If I did not make the drive onto the rocks correctly—there was a chance that the water would grab my tail, spin me around and flush me down the pinch backwards. If I did not like the situation, I could get back in my boat and eddy back across river. We could still portage river left.

I drove up on the rocks and got out without any trouble. I then attempted to cross the channel to get to the rocks on the right bank. The only way to do it was to commit and jump. If I did that, I was not sure I could get back across. Everything still looked good so I waved David over. I grabbed him and he got out. I jumped across. The passing of boats and gear was very dangerous. If you slipped or dropped any gear, it was going down the pinch and heading for the canyon. We took our time and were very methodical. It was David’s turn to jump. I asked him if he wanted a rope or sling. The look he gave me made me feel like I insulted him. David competed as a decathlete at a collegiate level.

Seal launching back into the river meant immediately committing to the next ledge drop. I went first and was moving fast. I thought it was going to be a boof. Instead, it was a 10-15 foot vertical slide that had a kicker rock in the bottom. I halted my boof stroke at the last second dropped my bow hitting the kicker rock perfectly. I then looked downstream to see a log in the next drop. I caught the only eddy on river left. I knew David was right behind me—so I scrambled to get out of my boat to free up the eddy for him. About the time I got out of my boat I saw him come over the drop. He was further right than I was, and ended up flipping. I do the “roll up, roll up” under my breath while scrambling for my throw rope. David nailed his roll and was facing upstream. He could tell by my facial expression and the fact that I was out of my boat that he needed to eddy out immediately. With a couple quick strokes he caught the eddy and hopped out.

This next drop is a small ledge. It hits the canyon wall and makes a ninety degree right turn. The log is at a “T” to the drop. We looked up and checked both sides of the canyon. There was no easy option. I started studying the logs. There was a small eddy in the back left where the wall makes the 90-degree turn to the right. There is the log and a piece of another log wedged end to end on the canyon walls. It looked like it would be too dangerous to try and paddle to the back eddy and get out of my boat at the log. There was no way to get any footing. Also, if you flipped there, you and your gear would be swept into the logs. If I swam out to the eddy—near the left wall—I could then grab the partial log and use it to pull my self up onto both logs. I jumped in and swam along the left wall about 15 feet. Once secured to the logs, I had Dave attach my boat to a throw bag—which he then tossed my way. It took a couple minutes to get my gear situated. I ended up securing my boat to my rescue harness while it floated freely on the downriver side of the logjam. This allowed me to use both hands freely while balancing on the logjam. We debated tossing my paddle the 15-20 feet—then quickly decided that attaching a line and not losing a paddle was the better option.

David was nervous about the swim, and the “paddling the drop” option wasn’t any more settling. He felt confident enough to seal launch and paddle to me. I then lifted him over the log, and he paddled to the eddy shortly downstream. I had to precariously place my boat on the two crossed logs and get in it, put my skirt on, grab my paddle without falling off the log. With patience and care, I joined David in the eddy below.

A few drops later, we came to another log. This one was big and river wide. There was a pretty straightforward ledge but all the water was feeding right which then culminated at the log and the right wall. Upon first glance, it looked like it you might be able to charge it and boof over the log. Upon further inspection there was a hole right before it that would stall your moment. If for any reason you did not make it, you would be pinned there and have no way for someone to rescue you. The other possible option was to get in the river left eddy before the log. It was an extremely hard move because you would need to enter on the far right and drive all the way across the current in front of the log—thus putting yourself right in harms way. We looked around at the canyon walls; they were steep. We debated waiting it out to see if the water dropped again — hoping it would make the left eddy easier to attain. After discussing, we decided to attempt portaging.

This meant someone had to free climb 75+ feet up the cliff. There was a gap but it looked questionable. I started climbing. The first 10 feet or so was straightforward. It then started to get steeper—and steeper. The canyon walls were made up of small, loose, crumbling scree. The little bit of out cropping rocks it did have, were all shale. As soon as you thought you found a good hold it would crumble in your hands. I was about 50 feet up when I hit the crux of the climb. I had a small section to traverse right to a ledge. I had my feet on some sketchy spots and was searching for a good handhold. I could not find one. For some reason, at that point, I looked down. I think it was to determine a line for a potential down climb. I quickly realized how high I was, and that down climbing was not an option. I panicked for a second and had to pull my body as close to the cliff as I could. I concentrated on my breathing. My legs began to shake due to fatigue, and fear. I concentrated harder on my breathing. I slowly got it under control. Even though I was not breathing as slow as I wanted, it would have to do. I could not just stand there. I quickly determined what my next best option was. Above me was a shrub. If I could get a hold of it, it would provide the decent handgrip that I so desperately needed. The wall near my chest was slightly overhanging. I pulled my hips in tight and started to lean up—reaching. I pulled back in. I wasn’t ready yet. I concentrated on my breathing for 2-3 more breaths. My legs tightening, I leaned up again, slowly—making sure to shift my weight in just the right amounts. I extended my 6’4″ frame to the fullest and grabbed the branch. Pulling my chest close to the overhang and my hips in tighter, I slowly moved my foot to the next hold. Once stable, I quickly pulled the other foot over. Things now became easier and I continued up.

There was no “top” per say. The mountains just go up and up in this wilderness. There is just scree, small shrub trees and small pockets of semi-vertical versus vertical. I needed to determine if there was a place for us to get back down to the river, and how far we would have to traverse to get there. Upon inspection, we were in luck. There was a ravine down to the river with a rock ledge and enough space to launch. The ravine required more rope work to descend it.

I went back and told David my plan. Even 75+ feet below, he knew there wasn’t another option. I found a four inch shrub off to the right that I could use for an anchor and sent down my rope. It was about 10 feet too short (60 foot rope). I pulled it back up, attached my sling to it, and sent it down again. This time, David was able to connect his rope and sling. I pulled up all the goods and got my rope work prepped. I had two ropes, one 60 feet (1/2” thick), one 75 feet (1/4” thick), two pullies, two prussics and a few carabiners.

I set up the sling around the tree with a pulley and prussic on the 75 foot (1/4) rope. I threw it down to David. He connected one of the boats (~100 lbs with gear). I started to pull it up. It was not working. First, the anchor point was not in line, so it was putting stress on a sideways pull. The second thing was the 1/4″ rope was cutting the shit out of my hands. It had a rough sheath and was too small for this type of use. I pulled it about 10 feet and stopped. David hollered at me and I peered down to him and said, “It’s not working, give me a minute”.

I had to fix the problem. I could make a 3-1 advantage with the other pulley and prussic, but then I would have to manage it and pull over and over with not much “working” area on the side of the hill. It wasn’t the ideal option. I needed to get a better pull angle. I looked around to find the next best spot. There was a small 1-inch shrub that I had overlooked. It was the only other option, so I had to make it work. Switching to the 1/2-inch line was necessary to keep from cutting my hands as bad. I released the prussic and lowered the boat back down to David. I hollered down to start unloading boats.

I started derigging. I originally tried to use both slings to connect the 4″ tree and the 1″ tree but they were not long enough. I thought about removing my pfd and using that to bridge the gap. After some consideration, I thought I could test the 1″ tree and see how solid it was. I tied myself into the 4″ tree and put all my, 200 lb weight onto the 1″ tree. It held solid and did not move. That would work. I then connected the 1/4” rope and the 1/2″ rope, and then tossed the 1/2″ rope down. By the time I was done rigging everything up again, David was done unloading the gear from the boats. He connected the empty boat this time. The new rigging allowed me to only have to pull about 10 feet with the shitty 1/4″ rope. If I wrapped it multiple times around my hands it did not cut too bad. Once the connection point of the two ropes reached the pulley, I rigged the other prussic onto the 1/2″ rope. I pulled until I could get that prussic onto the carabiner to hold. I then removed the 1/4″ rope, ran the 1/2″ through the pulley, and the boat was up in no time. The right tool for the job always makes it easier.

We did this a total of 5 times to get the gear up (2 boats, 2 piles of gear, 2 paddles). Each time a piece came up, I had to disconnect it and then traverse or up climb 10-15 feet. I had to find a shrub to stash it behind or attach it so it would not slide off the cliff. I was glad to have a rope on David as he climbed up—though he did not have much trouble. If nothing else, it provided mental security.

Everything was up. I led David over to the ravine to make sure he was comfortable with plan while also trying to find a line to traverse. He glanced it over. He—like me—was not happy with it, but agreed it would work. We started traversing gear—one piece at a time—being careful with every step. The ravine had a really nice tree that I used for an anchor point. I set things up. When I was ready, Dave connected himself to the end of my rope work. He started climbing down. With some back and forth, using trees/shrubs, and kicking some scree, he got down. I lowered boats and gear down to him, one piece at a time, same as coming up. I had to use the 1/4″ rope again due to its longer length. Because it was descending, I had an easier time controlling the weight. At one point, the gear kicked down some rocks and poor David dove into the cliff for protection. He still took a couple big rocks to the head and shoulder.

It was my turn to descend and I did not want the excitement that I had coming up. It looked like I could plan it right using trees and shrubs to down climb while using the thicker (1/2”) rope. I folded the rope in half and slung it around a tree. This gave me about 30 feet at a time to down climb before running out of rope. I did this until I got to a shelf or anchor point, and then pulled the rope around the tree to me. I would then traverse to the next possible anchor point and repeat. I had to free climb the last 10-15 feet before safely regrouping with David and the rest of our gear.

At this point, David and I took a quick break for some food and water. The portage probably took about 3 hours. We had to go slow, be cautious, and do things repetitively to make this feasible.

We had spent almost a full day doing three portages managing about 1/2 mile of river. We were hoping to be out of the canyon soon and get some miles under our belt. The next series of rapids were very fun and enjoyable. As we moved down stream the Canyon walls slowly deteriorated, but we still had about 3-4 more portages ahead due to logs.

We soon came out to the confluence of the Chetco. I gave David a hug. At this point, things became a lot easier. We paddled for about another 1/2 hour looking for a campsite. It rained all night, our coldest night. Considering we were only planning to spend one night and this was our third, we still had plenty of food. David cooked up some rice and beans, a two person dehydrated meal, which we shared. We ate the last crumbles of jerky and each had a cliff bar for desert.

The next morning it was time to finish out and get home. The Chetco at this level was awesome. I would call it 4/4+ bigger water read and run. About 14 miles after our day 4 put-in, we got down to the 1st steel bridge. We expected someone to be there looking for us. We had two more class 5 rapids left, Candy Cane and Cone Head. We got to Candy Cane and got out to scout. It was horrible looking with two big pour over holes and a big hole at the bottom. We thought about trying to sneak down the right side. Upon ferrying over, it looked really bad with some nasty undercuts. We carried around.

I thought there was a small gap between Candy Cane and Cone Head but there is not. Once we put on, I had to make a quick decision between running the rapid and catching the eddy. As I started in, I could see the line: start center and work right. There were big waves but I ended up nailing the line. I turned to wait on David. He said he eddied out on the right to boat scout. He saw me charging right. He came out of the eddy to the middle but then had to change direction to charge back to the right. As he came in, he hit a crashing wave, which sent him back to the middle. The wave sent him backwards right into the pour over hole in the middle. He glamorously attempted to fight it out, but it wasn’t happening. It was so powerful that when he went to pull the sprayskirt, the hole had him pinned against the back deck. He had to wait until it shifted him so he could reach it. He flushed down and around the center rock. It was so violent; it ripped his go pro off his helmet. There was a big pool below. We collected his gear and got him back in his boat.

We were about 100 yards from the takeout when we heard the helicopter coming. It circled around us and we both knew it was looking for us. As we pulled up to our takeout, there was a sheriff and two guys getting ready to launch a jet boat. They were looking up at the helicopter as it circled and did not notice us until we hit the shore. They said they were looking for us. After the helicopter landed, a guy came over and spoke to David directly. I guess David’s dad was on a fire crew for many years and pulled some strings to get the helicopter and most of the rescue team.

I tried to thank each person that had come to assist us. I felt bad about not being able to let others know.

Because we were in there so long, David’s truck got snowed in. I hope we can get it out soon and it does not have to sit there all winter.

Notes/Thoughts/Comments

——————————

The first day, the water was too high. The next day was high. The last day was medium high. I think the Chetco gage is only a loose way to tell what you have in there. Make sure there is no rain behind you and don’t be afraid to sit it out or retreat out of there if things are too high. I think ideal flows are 4K – 6K on the Chetco gauge, but they can change fast—especially in the fall.

I would recommend taking a climbing rope and an ascender/belay device.

This is NOT an alternative to doing the Chetco. It is a separate river and different beast. The magic of the Chetco is in its upper reaches. This section puts you below the best parts of the Chetco.

The Chetco from Box Canyon down at high water is awesome. Too bad there is not easier access.

There would have been more photos and video but my phone died because I had to use it for land navigation in the beginning of the trip and Dave lost his Go Pro.